Herman Vuijsje, Dutch sociologist and journalist, presented this biography of Joseph van Cleef at St Martin Vésubie in September 2015.

It was first published, in Dutch, in De Groene Amsterdammer, in issue 16 of 15 april 2015.

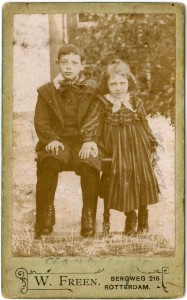

Joseph van Cleef’s father and mother grew up a few streets from where I live, in the Jewish quarter of Amsterdam. Except for the War, Amsterdam never had a ghetto, where Jews were forced to live, but the Jews lived together in one of the poorest neighbourhoods of the city. Joseph was born in 1896. Here he is, with his sister Clara.

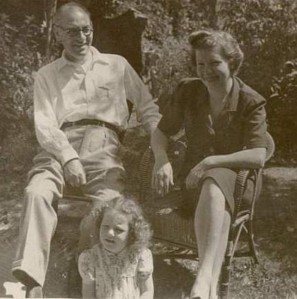

When I started my investigations into Joseph’s life history, I soon came across a picture of him as a grown up man. He looked like my father, who also was Jewish, in his younger years. Maybe, I thought, when I would have lived in that time, I would have looked the same. But what would I have done?

Joseph’s grandfathers were both diamond cutters, his father was a street merchant. The Amsterdam Jews did not belong to the upper middle class, like those in most Western European countries; they were an industrial proletariat. Joseph also ended up in the trade, but he managed to work himself up and moved to Brussels, where he married a Catholic girl, Agnes Smekens. In 1939, their daughter Colette was born.

In 1940, after the Germans occupied Belgium, the family fled to Nice, where they were ordered, in March 1943, to move to Saint Martin Vésubie. They took up residence in a chalet called Villa Galante, which I have not been able to locate.

Here in Saint Martin, Joseph met another refugee, Stella Silberstein, a Viennese physiotherapist who managed to survive the war and published her war memories under the title Hotel Excelsior, named after the infamous hotel in Nice that served as a transit camp on the way to Drancy and Auschwitz.

With her book, Stella Silberstein gave Joseph a face. Literally: she described him as ‘a tall man with thick brown hair and a rogue‑like face. He used to look at people from the corners of his eyes, which gave him, because of his thick glasses, a somewhat shy appearance.’

But Silberstein gave Joseph a face also in a figurative way. In her book, he comes forward as a man who finds it very difficult to cope with the dangers he has to confront. He is always hesitating what to do. At every stage of the flight, he must be persuaded. Joseph is human ‑ how should I translate this? Human in the sense that he shows the limits of what people are able to do in an inhuman situation.

His new friend Stella is quite the opposite. She is always on the alert, looking for the best possibilities to survive. The same is true for her friend Richard, a doctor who also fled Vienna and landed in Saint Martin Vésubie.

Stella and Richard are aware they won’t be able to stay in Saint Martin forever, they are preparing for a renewed departure. But when they discuss this, Joseph shakes his head. ‘I’ve had enough,’ he says. ‘I will not leave again.’

Stella understands why. Joseph has never been separated a day from Agnes and Colette, ‘a bubbly girl of four years.’ If he would flee over the mountains, they would be left behind, as Agnes is not Jewish, and little Colette only half.

But when the day comes, the day of the march to Italy, Joseph is persuaded and heads with Stella and Richard towards the Col de Fenestre. They spend the night there and proceed the next day to Entracque, the first village in Italy.

There, Joseph and his friend reach a nunnery, a little convent, where they are warmly received. The sick get freshly made beds, writes Stella, ‘the weary and exhausted people were assisted by the sisters. They felt safe, old and young relaxed.’

Soon, the refugees realize that the abbess, mother Mary, and the other sisters also extend their compassion to others. They help partisans in the mountains and ask Richard and Stella to provide medical assistance. So the next day they leave with a mule, blessed by a concerned mother Mary. The second day they go again, but this time, when they return, they find everyone packed and ready: the Germans have appeared in the valley.

Yet, Richard and Stella let themselves be persuaded for a third time to visit a group of partisans. Along the way they are noticed by German soldiers and taken to the village square of Entracque.

‘There we were reunited with our friends from Saint Martin,’ writes Stella, ‘arranged in rows.’ Silently, they stand there, no one opposes. Joseph is there also. Hauptmann Müller, the German commander, is delighted. The more Jews be puts forward, the better his mood.

It is a misty autumn day, winter is already in the air, when they head for Borgo San Dalmazzo. They walk along the fields, farmers are working, everything seems peaceful and quiet. ‘Nobody took notice of us, but all of us were on the verge of a nervous breakdown.’

In the abandoned barracks where the Germans have set up a makeshift transit camp, Richard and Stella put up a medical post. Also, letters are being exchanged with relatives who stayed behind in Saint Martin Vésubie. Don Francesco Brondello, the young chaplain of the village of Valdieri, is an accomplished skier and smuggles letters back and forth across the border.

Joseph also receives news from Agnes. She writes that he can escape with the help of Brondello. But Joseph decides not to accept the offer, as the Germans are known to take retaliations against other prisoners in such cases. He advises Agnes to return to Belgium.

On November 21, 1943 Joseph, Richard and Stella are taken away to the Borgo train station and crammed into a train that takes them to Nice. There they march to the Avenue Durante, where the Gestapo set up its headquarters in the Hotel Excelsior. Compared to the hotels where the life of Saint Martin Vésubie was going on, this is the superlative of surrealism. Built in lavish Belle Époque style, Excelsior is a tribute to the good life of the Cote d’Azur.

But in the stairwell on each floor there is a sign, saying ‘It is forbidden to look out the window. Violators will be shot.’ And in reality, they are.

While Joseph, Stella and Richard are awaiting further transport in Excelsior, in the streets of Nice horrific pogroms take place. Men who are seized, are forced to drop their pants. Whoever is circumcised, goes on transport.

Richard is involved. As a doctor, he should determine who is circumcised as a Jew and who for medical reasons. He can save many. Stella also manages to prolong her stay by making herself ‘indispensable’ as a cleaner and a masseuse.

Joseph attempts a different way. He addresses the Austrian Hauptscharführer Ernest Ullmann, the deputy commander of the Hotel. With his tall, blonde appearance, writes Stella, he seems to radiate something human. Joseph tells him that he has a non-Jewish wife and asks permission to visit her. Ullmann responds courteously. Joseph will be released, but for administrative reasons, this will not be possible before he is transported. At the first stop, he will be allowed to leave the train.

‘And what if they do not do that?’ Richard asks.

Joseph shrugs: ‘What have I got to lose?’

‘Try to work here, make yourself indispensable!’

But Joseph answers: ‘That I will not, absolutely not. Let come what comes.’

Stella also tries to make him change his mind: ‘Do not be so stubborn! Anything is better than Pitchi‑poi.’ Pitchi‑poi is the mythical designation, used by the Jews in France for the uncertain destination in the east. But Joseph is unable to produce the strength for a new beginning. He had to force himself already to undertake the flight over the mountains; now he can no more.

Stella writes: ‘Yet I feel his sad look, which hurt me almost physically.’

‘My fate is sealed,’ he said, ‘there is nothing to change.’

The following day, November 30, 1943, eight days after his arrival in Nice, Joseph was transported to the transit camp at Drancy near Paris. Stella saw him standing ready to leave, a wistful smile on the lips.

Stella and Richard succeed in avoiding deportation during half a year. In that period, Richard, who as a doctor was allowed to move outside the hotel, got deeply involved in the Resistance movement. In March ‘44 he was arrested and shot.

A month later, Stella was transported to Drancy and then to Auschwitz. There, too, she managed to establish a position: as a masseuse for the camp leadership. She was eventually liberated at Bergen‑Belsen concentration camp.

In Drancy, Joseph has a last meeting with Agnes, who has gone to Paris from Saint Martin Vésubie. She comes with a representative of the Belgian embassy, who testifies that Joseph is married to a non-Jewish woman, a reason for exemption from transport to the east. But the camp commander says that Joseph has not been arrested as a Jew, but as a member of a Resistance group. However, Agnes may join him. But Joseph tells her to go away and take care of Colette.

On December 17, 1943 Joseph was sent to Auschwitz, where he arrived three days later. There, he probably was murdered immediately after arrival, 48 years old.

After the war, Agnes and Colette returned to Belgium. Agnes died in 1975. Colette still lives in Brussels, she has two children and three grandchildren.

Why did I want to write Joseph’s story? Firstly, from the same motivation as Adriana Muncinelli, the Italian historian who first told me about him. She reconstructs the biographies of the hundreds who completed the trek across the Alps but in the end did not survive the war. With her investigation project Behind the name, she wants to return a face and a life to these forgotten people.

I also had a second reason. Les Juifs de Saint Martin Vésubie[DB4] can correct the image of the Jews who let themselves being dragged to their destruction without any resistance.

‘These people were fighters,’ said Adriana Muncinelli. ‘And with insight. They had built self‑confidence, from which they dared to take risks. They recognized the risks in time and acted accordingly; wary, but also able to give confidence to people who deserved that.’

Two years ago, I heard Jacques Blum talking here, who as a boy participated in the march of ‘43. ‘I hate the mountains.’ he said. ‘You see a mountain and when you are atop, you discover that behind it lies a higher top again, and another.’

That image struck me as a perfect metaphor for the way these people had to flee, often on the run for years, each time with a new obstacle in sight that needed to be overcome, and a new land where they had to build a life. On the way, Jacques Blum noticed people about to give up: ‘I won’t go any further, what is it good for?’ And he understood: ‘Everyone who survived, had to resist the temptation to collapse and abandon all hope.’

Some, like Stella Silberstein, managed to maintain this almost superhuman effort until the end. Joseph could not get it done. Not that he lacked courage: he repeatedly subordinated his fate to the chances of others, of his family. Joseph was not devoid of courage ‑ he was discouraged.

This was my story about Joseph van Cleef. When I look him in the eyes, I think I can identify with him. Because he was a Dutchman and a Jew, because he lived a few streets from where I live, and because he looked like my father.

But in the first place I can identify with Joseph because he was so human in his inability to deal with the utmost evil. Yes, he probably was kind of stubborn. He just refused to play the game that the Germans had set out the rules for. I think, in some way he felt that was beneath his dignity as a human being.

Herman Vuijsje